United Nations A/66/365

General Assembly Distr.: General

16 September 2011

Original: English

11-50111 (E) 300911

*1150111*

Sixty-sixth session

Agenda item 69 (c)

Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights situations

and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives

Situation of human rights in Myanmar

Note by the Secretary-General

The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the members of the

General Assembly the report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human

rights in Myanmar, Tomás Ojea Quintana, in accordance with paragraph 30 of

General Assembly resolution 65/241.

A/66/365

2 11-50111

Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human

rights in Myanmar

Summary

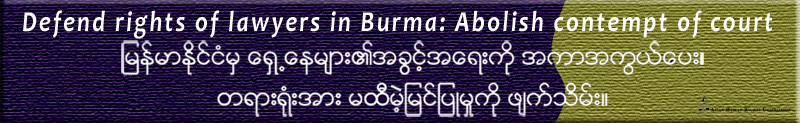

This is a key moment in Myanmar’s history and there are real opportunities for

positive and meaningful developments to improve the human rights situation and

deepen the transition to democracy. The new Government has taken a number of

steps towards these ends. Yet, many serious human rights issues remain and they

need to be addressed. The new Government should intensify its efforts to implement

its own commitments and to fulfil its international human rights obligations. The

international community needs to continue to remain engaged and to closely follow

developments. The international community also needs to support and assist the

Government during this important time. The Special Rapporteur reaffirms his

willingness to work constructively and cooperatively with Myanmar to improve the

human rights situation of its people.

Contents

Page

I. Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

II. Assessing the transition to democracy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

III. The situation of ethnic minorities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

IV. Human rights situation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

A. Prisoners of conscience . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

B. Conditions of detention and treatment of prisoners . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

C. Other issues related to civil and political rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

D. Economic, social and cultural rights . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

V. Truth, justice and accountability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

VI. International cooperation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

VII. Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

VIII. Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

A/66/365

11-50111 3

I. Introduction

1. The mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in

Myanmar was established by the Commission on Human Rights in its resolution

1992/58 and extended most recently by the Human Rights Council in its resolution

16/24. The current Special Rapporteur, Tomás Ojea Quintana (Argentina), officially

assumed the function on 1 May 2008.

2. The present report is submitted pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution

16/24 and General Assembly resolution 65/241, and covers human rights developments

in Myanmar since the Special Rapporteur’s fourth report to the Council in March 2011

(A/HRC/16/59) and his report to the Assembly in September 2010 (A/65/368).

3. The first regular session of Myanmar’s new national Parliament was convened

on 31 January 2011 and ended on 23 March. On 30 March, the State Peace and

Development Council was officially dissolved and power was transferred to the new

Government; the new President, two Vice-Presidents and 55 other cabinet members

were sworn into office in an inauguration ceremony in Nay Pyi Taw. Myanmar thus

reached the last step of its seven-step road map to a “genuine, disciplined, multi-party

democratic system”.

4. President Thein Sein’s inaugural speeches to Parliament on 30 March, to

cabinet members and Government officials on 31 March and to chief ministers of

regional and State governments on 6 April set out a number of commitments to

reform and outlined the new Government’s public policy agenda. Of note, the

safeguarding of fundamental human rights and freedoms, respect for the rule of law

and an independent and transparent judiciary, respect for the role of the media, good

governance, the protection of social and economic rights, the development of

infrastructure and delivery of basic services, including in ethnic areas, and the

improvement of health and education standards, were among the priorities identified.

5. From 16 to 23 May 2011, the Special Rapporteur travelled to Bangkok, Chiang

Mai and Mae Hong Son, in Thailand, to meet with various stakeholders, including

representatives of ethnic minority groups, community-based and civil society

organizations, diplomats and other experts. The Special Rapporteur thanks the

Government of Thailand for facilitating his visit, including a meeting with the

Minister for Foreign Affairs, Mr. Kasit Piromya.

6. From 21 to 25 August 2011, following an exchange of communications with

the Government arising from his previous visit, in February 2010, the Special

Rapporteur conducted his fourth mission to Myanmar at the invitation of the

Government. In Nay Pyi Taw, the Special Rapporteur met with the Minister for

Foreign Affairs, the Minister for Home Affairs, the Minister for Defence, the Deputy

Chief of Police, the Minister for Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement, who also

holds the position of the Minister for Labour, the Attorney General, the Chief

Justice of the Supreme Court, the Union Election Commission and with some of the

presidential advisers. He also met the Speakers and members of the Pyithu and

Amyotha Hluttaws, including representatives of ethnic political parties, and

observed the second regular session of the Pyithu Hluttaw. He delivered a lecture on

international human rights at a training course organized by the Ministry of Home

Affairs, which was attended by officials of different ministries and townships. In

Yangon, the Special Rapporteur met Daw Aung San Suu Kyi to discuss a range of

important human rights issues, conducted a visit to Insein prison, where he met with

A/66/365

4 11-50111

seven prisoners of conscience, met with representatives of civil society organizations,

former prisoners of conscience and the United Nations country team, briefed the

diplomatic community and held a meeting with director-generals of different

ministries, at the conclusion of his mission.

7. Following legislative elections, held on 7 November 2010, and the formation

of the new Government on 1 April 2011, the Special Rapporteur notes that a number

of steps have been taken that have the potential to deepen Myanmar’s transition to

democracy and to improve the human rights situation. As such, at the end of his

mission to the country, the Special Rapporteur welcomed the Government’s stated

commitments to reform and the priorities set out by President Thein Sein, which

included the protection of social and economic rights; the protection of fundamental

human rights and freedoms, including through the amendment and revocation of

existing laws; good governance and fighting corruption, in cooperation with the

people; respect for the rule of law; and an independent and transparent judiciary. He

also welcomed the President’s emphasis on the need for peace talks with armed

groups and the open door for exiles to return to the country. The Special Rapporteur

reiterates, however, that these commitments must be translated into concrete action.

8. The Special Rapporteur thanks the Government of Myanmar for its invitation

and for the cooperation and flexibility shown during his visit, particularly with

respect to the organization of his programme. In addition to the visit, he continued

to engage with the Government through meetings with its ambassadors in Geneva

and Bangkok, and through written communications.

9. These communications include a joint urgent action letter with the Special

Rapporteurs on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or

punishment and on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion

and expression, regarding the hunger strike by political prisoners in Insein prison,

on 1 June 2011; and a joint urgent action letter with the Chair-Rapporteur of the

Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the Special Rapporteurs on the right to

freedom of opinion and expression, on the situation of human rights defenders, on

torture and on violence against women, its causes and consequences, on the case of

Hnin May Aung, on 21 July 2011. In addition, on 30 June 2011, the Special

Rapporteur sent a letter to the Government requesting an update on the status of the

prisoners of conscience mentioned in his previous reports.

10. The Special Rapporteur would like to thank the Office of the United Nations

High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), in particular at Geneva, Bangkok

and New York, for assisting him in discharging his mandate.

II. Assessing the transition to democracy

11. In its resolution 16/24, the Human Rights Council requested the Special

Rapporteur to make “an assessment of any progress made by the Government in

relation to its stated intention to transition to a democracy”. As a thorough

assessment may be beyond the scope of the present report, the Special Rapporteur

proposes to address a number of key issues, which, in his view, are essential features

of democratic transition in Myanmar: the functioning of key State institutions and

bodies; the situation of ethnic minorities, including ongoing tensions in ethnic

border areas and armed conflict with some armed ethnic groups; the human rights

situation; and truth, justice and accountability.

A/66/365

11-50111 5

12. The Special Rapporteur holds the view that central to any democratic

transition, anchored in important human rights principles, including participation,

empowerment, transparency, accountability and non-discrimination, is the effective

functioning and integrity of State institutions and bodies.

13. Many critics have noted that the new Government is comprised of many

officials from the previous military Government. Together with military appointees

who automatically occupy a quarter of seats, it is reported that 89 per cent of all

seats in the legislature are occupied by people with affiliations to the former

Government. Yet, the political landscape has changed. The new Government is

nominally civilian and there is an emergence of different actors and parties engaging

in the political process. Additionally, decision-making has supposedly been

decentralized to various ministries, and new institutions and bodies, such as the

National Defence and Security Council and the Supreme State Council, have been

created. These developments could further the process of transition, and they require

close observation, to see how they unfold.

14. Given their central role in any democracy, the Special Rapporteur has paid

particular attention to the establishment and functioning of the new national,

regional and State legislatures. He is encouraged that the national legislature

(comprised of the upper and lower houses — the Amyotha Hluttaw and Pyithu

Hluttaw) has begun exercising its powers within the framework of the Constitution

and notes what seems to be an opening of space for different actors and parties to

engage in the political process. For instance, Government ministers have appeared

before Parliament to answer questions, and parliamentary debates are covered by the

official media.

15. During its first regular session, important and sensitive issues relevant to the

promotion and protection of human rights were discussed, including land tenure

rights and land confiscation; the registration of associations and other local

organizations, as well as trade unions; discrimination against ethnic minorities in

civil service recruitment; the need for the teaching of ethnic minority languages in

schools in minority areas; the question of amnesty to Shan political prisoners; and the

granting of national identification cards to the Rohingya. Parliamentary committees, in

which opposition party members comprised one third of membership, were established,

including the Bill Committee, the Rights Committee, the Public Accounts Committee

and the Government’s Guarantees, Pledges and Undertakings Vetting Committee.

16. During its second regular session, which began on 22 August 2011, additional

committees, including the Fundamental Rights, Democracy and Human Rights

Committee, were formed. Important issues were also debated, including the

provision of medicines to hospitals, the rebuilding of primary schools in certain

constituencies, a private school registration bill and environmental conservation. A

member of the Pyithu Hluttaw presented motions to release all prisoners of

conscience and to deliberate the creation of a “prison bill for the twenty-first

century”, which would guarantee human dignity to all prisoners. The Speaker of the

House rejected the latter motion, stating that the Ministry of Home Affairs was

already drafting a revised prisons act.

17. While welcoming these developments, the Special Rapporteur notes the crucial

need to clarify a number of the Parliament’s practices and its internal rules and

procedures, including how often it will meet, the right of members to place items for

legislation and policy debate on the parliamentary agenda, and the precise role and

A/66/365

6 11-50111

functions of the various committees established. Also of importance is the need to

establish clear rules governing parliamentary immunity, particularly the specific

instances in which such immunity could be lifted. In this respect, he notes that laws

signed by then Senior General Than Shwe, in November 2010, stipulate that

parliamentarians will be allowed freedom of expression unless their speeches

endanger national security or the unity of the country or violate the Constitution.

The Special Rapporteur notes that these are broad categories that are not clearly

defined and could be used to limit debate. Members of Parliament should be able to

exercise their freedom of speech in the course of discharging their duties. This is

essential to ensure a properly functioning parliamentary culture — one in which

transparent, open and inclusive debates can be held on all matters of national

importance — an issue that the Special Rapporteur emphasized to the Speakers and

Members of Parliament.

18. There is also a strong need to enhance the capacity and functioning of the new

institution and its members. This was echoed by many interlocutors from different

sectors during the Special Rapporteur’s mission to Myanmar, some of whom

acknowledged a serious lack of knowledge and expertise of parliamentary practices

among Members of Parliament and the need for support by professional

parliamentarian staff. Accordingly, the Special Rapporteur strongly encourages the

Parliament to proactively seek cooperation and assistance from the international

community in this regard.

19. Another key institution is the judiciary. The Special Rapporteur observes that

the judiciary’s capacity, independence and impartiality remain outstanding issues in

Myanmar. The Special Rapporteur notes that there do not appear to be any major

structural transformations within the judiciary. The new Chief Justice was formerly

one of the justices on the Supreme Court, and the new Attorney General was

previously a Deputy Attorney General, with no further information on new

appointments to the courts.

20. Concerns regarding the functioning of the judiciary also remain. The Special

Rapporteur continues to receive information of criminal cases being heard behind

closed doors. In one case, the family of former army captain, Nay Myo Zin, was

barred from the closed court inside Insein prison, on 2 June 2011. Nay Myo Zin,

who left the army in 2005 and then volunteered for a blood donor group headed by a

member of the National League for Democracy, had been charged under the

Electronics Act. During the proceedings, judges heard a statement from Deputy

Police Commander, Swe Linn, who had conducted the search at his house, in early

April 2011, and found a document in his e-mail inbox entitled “National

Reconciliation”. On 26 August 2011, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. According

to reports, he appears to have been subjected to torture resulting in shattered lower

vertebrae and a broken rib, which led to his attending court on a hospital stretcher.

His requests for external hospitalization have also been reportedly denied.

21. Another concern regarding fair trials is the access to counsel. During the Special

Rapporteur’s meeting with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the Executive Committee of

the National League for Democracy, he was informed of the problem of the arbitrary

revocation of licences of lawyers who defend prisoners of conscience. The Special

Rapporteur urges the Government to reconsider these revocations and to guarantee

the effective right to counsel and to allow lawyers to practise their profession freely.

A/66/365

11-50111 7

22. The Special Rapporteur therefore encourages the Government of Myanmar to

implement his previous recommendations on the judiciary, the fourth core human

rights element as contained in his earlier report (A/63/341), and to undertake the

series of measures proposed, in order to enhance its independence and impartiality.

These include guarantees for due process of law, especially public hearings in trials

against prisoners of conscience. These and other measures are detailed in the Basic

Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary (1985); the Basic Principles on the

Role of Lawyers (1990); the Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors (1990); the

Procedures for the effective implementation of the Basic Principles on the

Independence of the Judiciary (1989); and the Beijing Statement of Principles of the

Independence of the Judiciary (1997). He also encourages the Government to seek

technical assistance, particularly in the area of capacity-building and training of

judges and lawyers.

23. Further, the Special Rapporteur is concerned at allegations of widespread

corruption, which, according to many sources, is institutionalized and pervasive.

According to studies by civil society organizations, payments are made at all stages

in the legal process and to all levels of officials, for such routine matters as access to

a detainee in police custody or determining the outcome of a case. As Myanmar

achieves greater economic development, there will likely be more conflicts and

contests that will need to be resolved in the courts. The Special Rapporteur therefore

welcomes the Government’s stated commitment to combating corruption and urges

that priority attention be given to the judiciary in this respect.

24. The Special Rapporteur notes that Myanmar has yet to establish complete

civilian control over the military, another key feature of democratic transition.

While there have been developments, such as changes within its leadership and the

abolishment of supra-ministerial policy committees, he notes the military’s role in

the legislatures (with military appointees occupying 25 per cent of seats), as well as

the role of the new Commander-in-Chief, General Min Aung Hlaing, who

independently administers and adjudicates all matters pertaining to the armed forces

and must be consulted by the President on appointments of the Ministers for

Defence, Home Affairs and Border Affairs (as provided in the 2008 Constitution).

Additionally, the Constitution establishes permanent military tribunals, separate

from oversight of the civilian justice mechanism, for which the Commander-in-

Chief will exercise appellate power. Further, and as outlined in greater detail below,

the Special Rapporteur has continued to receive reports of human rights violations

committed by the military, particularly in ethnic border areas. The Special

Rapporteur refers to his third core human rights element and encourages the

adoption by the military of the measures proposed, which could help to address the

above concerns.

25. The Special Rapporteur’s previous report to the Human Rights Council

(A/HRC/16/59) stated that the national elections, held in November 2010, failed to

meet international standards and highlighted restrictions on the freedoms of

expression, assembly and association. The Special Rapporteur’s previous report to

the General Assembly (A/65/368) stated that the electoral legal framework and its

implementation by the Election Commission and other relevant authorities in many

ways handicapped party development and participation, in the context of Myanmar’s

first election in over two decades. During his visit to Myanmar, the Union Election

Commission acknowledged difficulties and flaws in the conduct of the elections,

partly due to the number of polling stations and the inexperience of officials. The

A/66/365

8 11-50111

Special Rapporteur was also informed that 29 complaints had been filed with the

Election Commission, with decisions made in several cases. No further information

was provided although it was noted that such decisions had been published in the

official gazette.

26. Since the elections, the Special Rapporteur has received reports that the Union

Election Commission, despite new members appointed by Parliament, continues to

discourage the role of parties in the political process. For example, on 6 July 2011,

three elected representatives of the Rakhine Nationalities Development Party were

disqualified, by tribunal, following complaints by Union Solidarity and Development

Party representatives. The Election Commission also ordered the Rakhine

Nationalities Development Party representatives to pay compensation of 1.5 million

kyat (about US$ 1,765) each to the representatives of the Union Solidarity and

Development Party, reportedly for attacking the previous military Government and the

Union Solidarity and Development Party in their election campaigns during 2010.

27. With by-elections expected later this year for some 40 Pyithu Hluttaw, Amyotha

Hluttaw and State or regional Hluttaw seats, the Special Rapporteur strongly urges the

Union Election Commission to learn lessons from the November 2010 elections and

to play a role in ensuring that the upcoming by-elections are held in a more

participatory, inclusive and transparent manner. Complaints filed to the Election

Commission should be addressed in a timely, open and transparent manner.

Significant improvements to the electoral process would be important for

Myanmar’s democratic transition.

28. Finally, one new institution that has received positive attention is the new

Presidential Advisory Board, whose members include U Myint, as head of the Economic

Advisory Group, Sit Aye, who heads the Legal Advisory Group and Ko Ko Hlaing, who

heads the Political Advisory Group. The Special Rapporteur met with some of the

presidential advisers during his mission and held a frank and fruitful exchange of

views, including on important future initiatives. He believes that they have played a

key role in advising the President on the challenges facing Myanmar and the

priorities for reform. He therefore encourages them to continue their important

functions and to provide suggestions on how to translate or implement commitments

into concrete action.

III. The situation of ethnic minorities

29. The situation of ethnic minority groups, including armed conflict in the border

areas, presents serious limitations to the Government’s intention to transition to

democracy. In his previous reports, the Special Rapporteur highlighted concerns

regarding the systematic and endemic discrimination faced by ethnic and religious

minority groups, in particular in northern Rakhine and Chin States. Such concerns

included policies preventing the teaching of minority languages in schools, the

denial of citizenship to and restriction of movement of the Rohingya, restrictions on

the freedom of religion or belief and economic deprivation. The Special Rapporteur

has called upon the Government to ensure that ethnic minorities are granted

fundamental rights.

30. The Government has said that parliaments are the only venue for discussion on

national reconciliation. While ethnic political parties are represented in the national,

regional and State legislatures, the November 2010 electoral process excluded

A/66/365

11-50111 9

several significant ethnic and opposition groups that need to be included in any

meaningful dialogue. In addition, only a few members of ethnic political parties have

been nominated as Chief Minister of a State or region. These venues alone are therefore

not sufficient for resolving the situation of ethnic minorities. A comprehensive plan by

the Government is needed to officially engage these groups in serious dialogue and

resolve long-standing and deep-rooted concerns. More broadly, the Special

Rapporteur reiterates that ending discrimination and ensuring the enjoyment of

cultural rights for ethnic minorities is essential for national reconciliation and would

contribute to Myanmar’s long-term political and social stability.

31. The ongoing tensions in ethnic border areas and armed conflict with some

armed ethnic groups, particularly in Kachin, Shan and Kayin States, continue to

engender serious human rights violations, including attacks against civilian

populations, extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, arbitrary arrest and detention,

internal displacement, land confiscations, the recruitment of child soldiers and

forced labour and portering. The Special Rapporteur also continues to receive

disturbing reports of landmine use by both the Government and non-State armed

groups, and subsequent casualties throughout the country. For example, on 23 June

2011, a 72-year-old man lost his right foot after stepping on a landmine outside

Shwe Aye Myaing village, Kawkareik Township; and on 20 June 2011, a 21-year-old

man in Gklaw Ghaw village, Kawkareik Township, had to have his right leg

amputated after stepping on a landmine.1

32. Since 9 June 2011, armed clashes have erupted between the Myanmar military

and elements of the Kachin Independence Army, one of the largest and most powerful

armed ethnic groups, marking an end to a ceasefire in place since 1994. According to

reports, there are over 15,000 internally displaced people near the border with China,

with several thousands more hiding over the border. Their conditions are believed to

be perilous, with little aid available in the remote mountainous area. The United

Nations approached the Government, offering assistance to all those in need.

According to reliable sources, the Government’s position is that assistance is

currently provided at the local level, and when needed they will seek further

assistance from relevant partners. Allegations of abuses against civilian populations

throughout Kachin State include reports of 18 women and girls having been gangraped

by army soldiers, and of four of those victims being subsequently killed.

33. Fighting that erupted immediately after the November 2010 elections

continues in southern and central Kayin State, in areas controlled by factions of the

Democratic Karen Buddhist Army that refused to transform into border guard

forces. Recently, former units of the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army that had

agreed to the border guard forces scheme have defected and joined with the Karen

National Liberation Army. An estimated 8,000 people have been displaced in this

region, drastically increasing their vulnerability to human rights abuses, such as

arbitrary detention and arrest by the military, and risks from landmines.

34. In northern Kayin State and eastern Bago Division, internal displacement and

severe food shortages continue. Despite fewer reports of targeted attacks on

civilians, it appears that ration re-supply operations have continued as normal,

including the use of civilian porters to carry equipment and walk or drive ox-carts in

front of military trucks, to clear for landmines.

__________________

1 Karen Human Rights Group, Update No. 79, 27 June 2011.

A/66/365

10 11-50111

35. On 13 March 2011, the military broke a 22-year ceasefire with the Shan State

Army-North, with the mobilization of and attacks by 3,500 new troops. According

to community-based organizations with whom the Special Rapporteur met in Chiang

Mai, in May 2011, more than 100,000 civilians have been affected, with increases in

forced labour, forced relocation, property confiscation, arbitrary arrest, torture,

extrajudicial killings on suspicion of support for the opposition and the gang rape of

three women, details of which he finds particularly abhorrent.

36. In Mon State, authorities under the Southeast Command announced an order via

loudspeakers and posted notices in public locations in various townships, to members of

ceasefire groups, to turn in their weapons to police stations or Military Affairs Security

offices by 3 July 2011. However, no weapons were reported to have been handed over.

37. The Special Rapporteur welcomes President Thein Sein’s commitment to keep

the door open to peace and his statement of 17 August 2011 on the need for peace talks

with armed groups. He notes, in this respect, Notification 1/2011, issued on 18 August

2011, inviting armed groups to peace talks. He also welcomes as a first step the

establishment by Parliament of the Committee for Eternal Stability and Peace in the

Union of Myanmar, on 31 August 2011, which aims to mediate between the

Government and ethnic armed groups. He urges the Government to accelerate

efforts towards finding a durable political resolution rather than a military solution

to the complex undertaking of forging a stable, multi-ethnic nation. The Special

Rapporteur also reiterates his call for the Government and all armed groups to

ensure the protection of civilians, in particular children and women, during armed

conflict. He calls upon the Government to abide by international humanitarian law,

especially the four Geneva Conventions, to which Myanmar is party. In particular,

common article 3 of the Geneva Conventions provides for the protection of civilians

from inhumane treatment and violence to life and person. He further reiterates his

previous recommendation that the Government sign and ratify the Convention on

the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel

Mines and on Their Destruction (Mine Ban Treaty) immediately and work with

international organizations to develop a comprehensive plan to end the use of

landmines and to address their legacy, including the systematic removal of mines

and rehabilitation of victims.

IV. Human rights situation

38. Respect for human rights, including both broad categories of civil and political

rights and economic, social and cultural rights, is a crucial feature of any democratic

transition. The Special Rapporteur notes that the Government has made important

commitments and taken a number of steps that have the potential to improve the

human rights situation.

39. In his inaugural speech to Parliament on 30 March 2011, President Thein Sein

emphasized the safeguarding of the fundamental rights of citizens, noting that the

Government will “guarantee that all citizens will enjoy equal rights in terms of the

law” and will “amend and revoke the existing laws and adopt new laws as necessary

to implement the provisions on fundamental rights of citizens or human rights”. On

8 June 2011, during the adoption of the outcome of Myanmar’s universal periodic

review by the Human Rights Council, Attorney General Tun Shin reaffirmed Myanmar’s

commitment to the promotion and protection of human rights. In this respect, the

A/66/365

11-50111 11

Special Rapporteur is encouraged to note that Myanmar accepted 74 recommendations

out of 190 received and urges the Government to ensure their implementation.

40. Despite these positive statements, there are ongoing and serious human rights

concerns that need to be addressed.

A. Prisoners of conscience

41. Of key concern to the Special Rapporteur and to the international community

is the continuing detention of a large number of prisoners of conscience. There are

at least 1,995 such prisoners of conscience, according to current estimates. While

the Government continues to assert that there are no political prisoners in Myanmar,

the Special Rapporteur has consistently held that these are individuals who have

been imprisoned for exercising their fundamental human rights or whose fair trial or due

process rights have been denied. Their continued detention, in his view, is an important

barometer of the current condition of civil and political rights in the country.

42. On 16 May 2011, President Thein Sein announced an amnesty that commuted

death sentences to life imprisonment and reduced all prisoners’ sentences by one

year. The measure resulted in the release of an estimated 100 prisoners of

conscience, including 23 members of the National League for Democracy. While

encouraged by this political decision, the Special Rapporteur notes that it fails to

resolve the problem that prisoners of conscience, who should be released, continue

to be arbitrarily detained, which disappoints international and national expectations.

43. On 30 June 2011, the Special Rapporteur requested updates on the status of the

prisoners of conscience that he has mentioned in previous reports and statements,

including information about whether they remain in detention and where, whether

their sentences have been or will be reduced, and the overall state of their health.2

In its response of 3 August 2011, the Government stated that one individual could

not be verified, one had been listed twice, 14 had been released, while the rest

remained in prison.

44. The Special Rapporteur would like to remind the Government of the human

dimension of its continuing to hold prisoners of conscience, many with

unacceptably long sentences. Two of the longest-serving prisoners are Thant Zaw

and Nyi Nyi Oo, members of the youth group of the National League for Democracy

who were wrongfully convicted of bombing a Tanyin petroleum factory in July 1989.

Now in their mid-40s, they have spent the past 22 years in prison, much of the time

reportedly in solitary confinement. In the absence of any actual evidence of

involvement in the bombing, confessions were extracted under torture at Aung

Thabyay interrogation centre and used to convict them on murder charges in a

closed court military tribunal hearing at Insein prison, without their having access to

legal counsel, and for which they were sentenced to death. The Karen National Union

__________________

2 These include Ashion Pyinya Sara, Aung Thein, Aung Tun Myint, Bo Min Yu Ko, Pone Na Mee

(Mya Nyunt), Tin Min Htut, May Win Myint, Than Nyein, General Sao Hso Ten, Hla Hla Win,

Hla Myo Naung, Htay Kywe, Kay Thi Aung, Khin Maung Shein, Ko Mya Aye, Kyaw Ko Ko,

Kyaw Kyaw, Kyaw Min, Ma Khin Khin Nu, Min Ko Naing, Zarganar, Mya Than Htike, Nilar

Thein, Nyi Nyi Htwe, Nyi Pu, Pho Phyu, Phyo Wai Aung, Sandar, Su Su Nway, Than Myint

Aung, Than Tin, Thant Zin Oo, Thurein Aung, U Gambira, Khun Htun Oo, Myint Aye, Ne Win,

Oakkantha, Tin Yu, Win Zaw Naing and Zaw Naing Htwe.

A/66/365

12 11-50111

subsequently claimed responsibility for the bombing. In August 1989, military

intelligence arrested Ko Ko Naing, a “bomb expert” of the Karen National Union,

who confessed to the crime and exonerated the members of the National League for

Democracy from any involvement. On 1 September 1989, the Government held a

press conference announcing Ko Ko Naing’s guilty verdict. On 5 September 1989,

Thant Zaw and Nyi Nyi Oo were again brought to a military tribunal and tried

concurrently with 14 other activists for participating in anti-regime underground

movements and received sentences of 20 years for high treason. Their total

sentences were later commuted to 30 years’ imprisonment. Thant Zaw is currently

incarcerated at Thayet prison, 547 kilometres from his family in Yangon. Nyi Nyi

Oo is currently incarcerated at Taungoo prison, 281 kilometres from his family in

Yangon. Both men have suffered poor health in recent years. They should be

released immediately and unconditionally.

45. Since the start of his term as mandate holder in 2008, the Special Rapporteur

has consistently called for the immediate and systematic release of prisoners of

conscience (his second core human rights element, see A/63/341). The Special

Rapporteur was informed in his meetings that the Ministry of Home Affairs is

investigating the status of prisoners in lists provided by various sources.

Nevertheless, he would like to see a concrete and time-bound plan for their release,

with special attention to be given to elderly prisoners and those with health

problems. In all meetings with Government interlocutors during his mission to

Myanmar, he conveyed his firm belief that the release of prisoners of conscience is a

central and necessary step towards national reconciliation and would bring more

benefit to Myanmar’s efforts towards democracy. He stressed that the release must

be without any conditions that may result in new ways of diminishing the enjoyment

of human rights.

B. Conditions of detention and treatment of prisoners

46. The Special Rapporteur remains concerned about the conditions of detention

and the treatment of prisoners. He notes continuing allegations of torture and illtreatment

during interrogation, the use of prisoners as porters for the military or

“human shields”, and the transfer of prisoners to prisons in remote areas where they

are unable to receive family visits or packages of essential medicine and

supplemental food.

47. In January 2011, an estimated 700 prisoners, from approximately 12 prisons

and labour camps throughout Myanmar, were reportedly sent to southern Kayin

State by the Myanmar military with the cooperation of the Corrections Department

and the police, to serve as porters. Also in the same month, around 500 prisoners

were sent to northern Kayin State and eastern Bago region. They replaced 500

prisoners who were sent to the same region the previous year. International

humanitarian law provides for the humane treatment of persons under the control of

an armed force and specifically prohibits “violence to life and person” murder, cruel

treatment and torture and humiliating and degrading treatment of those persons

having no active part in the hostilities.3

__________________

3 Human Rights Watch and Karen Human Rights Group, Dead Men Walking: Convict Porters on

the Front Lines in Eastern Burma, July 2011, available from: www.hrw.org.

A/66/365

11-50111 13

48. In Insein prison, the Special Rapporteur met with seven prisoners of

conscience: Aung Thein, Tin Min Htut, Ma Khin Khin Nu, Phyo Wai Aung, Win

Zaw Naing, Sithu Zeya and Nyi Nyi Tun. He heard disturbing testimonies of

prolonged sleep and food deprivation during interrogation, beatings, and the burning

of bodily parts, including genital organs. He heard accounts of prisoners being

confined in cells normally used for prison dogs, as a means of punishment. As in his

previous meetings with prisoners, he was told of inadequate access to medical care,

where prisoners had to pay for medication at their own cost.

49. The Special Rapporteur sent a joint urgent appeal letter to the Government on

21 July 2011 regarding the case of Hnin May Aung (also known as Noble Aye), a

member of the All Burma Federation of Student Unions and 88 Generation Students,

who is serving an 11-year sentence for violation of section 5/96 (4) of the Law

Protecting the Peaceful and Systematic Transfer of State Responsibility and the

Successful Performance of the Functions of the National Convention against

Disturbance and Oppositions (No. 5), section 505 (b) of the Penal Code, and section

6 of the Law Relating to the Forming of Organizations. Hnin May Aung is serving

her sentence in the remote Monywa prison in Sagaing region, 517 miles from

Yangon where her family lives. She was held incommunicado in a punishment cell,

essentially solitary confinement, with a ban on family visits for writing an open letter

addressed to President Thein Sein, strongly denouncing statements, made on 2 June

2011 by Vice-President U Tin Aung Myint Oo to United States Senator John McCain,

that there are no political prisoners in Myanmar. When Hnin May Aung’s father

attempted to visit her on 7 July, he was told by the warden of the jail and an

intelligence officer that her family visits had been banned because she had violated

prison regulations. The warden did not explain which rule had been violated. Her

father was also unable to deliver a package of supplementary food and essential

medication to Hnin May Aung, who suffers from jaundice.

50. The Special Rapporteur reminds the Government that it has a duty to ensure

Hnin May Aung’s right to physical and mental integrity. He recalls paragraph 1 of

Human Rights Council resolution 8/8, which “condemns all forms of torture and

other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, which are and shall

remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever and can thus never be

justified, and calls upon all Governments to implement fully the prohibition of

torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”.

Furthermore, article 7 of the Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners

provides that “efforts addressed to the abolition of solitary confinement as a

punishment, or to the restriction of its use, should be undertaken and encouraged”

(as affirmed by the General Assembly in its resolution 45/111). He also draws

attention to principle 19 of the Body of Principles for the Protection of All Persons

under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment, adopted by the Assembly in its

resolution 43/173, which states that “a detained or imprisoned person shall have the

right to be visited by and to correspond with, in particular, members of his family

and shall be given adequate opportunity to communicate with the outside world”.

Attention is also drawn to rule 37 of the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment

of Prisoners, adopted on 30 August 1955 by the First United Nations Congress on

the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, which provides that

“prisoners shall be allowed under necessary supervision to communicate with their

family and reputable friends at regular intervals, both by correspondence and by

receiving visits”.

A/66/365

14 11-50111

C. Other issues related to civil and political rights

51. In his previous reports and in his meetings with various Government

interlocutors, the Special Rapporteur highlighted several domestic laws that continue

to be used to restrict fundamental freedoms, among which: the State Protection Act

(1975), the Unlawful Association Act (1908), sections 143, 145, 152, 505, 505 (b)

and 295 (A) of the penal code, the Television and Video Law (1985), the Motion

Picture Law (1996), the Computer Science and Development Law (1996), and the

Printers and Publishers Registration Act (1962). The Government has said that it is

in the process of reviewing legislation to bring relevant laws into line with the

Constitution, and ostensibly with international human rights standards as the Special

Rapporteur repeatedly recommended (his first core human rights element). He notes

that, despite assurances that this review process was already under way in February

2010, there have not been any results announced. Nevertheless, the Special

Rapporteur was encouraged to hear that the review process continues, including

during the second regular session of Parliament. Given the Government’s stated

commitment to respect for the rule of law, and in line with his previous

recommendations on the issue, he hopes such efforts will be accelerated and clear

time-bound target dates for the conclusion of the review will be established.

Additionally, priority legislation for urgent review should also be identified,

including those provisions identified by the Special Rapporteur. Similar sentiments

had been expressed by the Committee on Freedom of Association of the International

Labour Organization (ILO), in May 2011, when it urged the Government to repeal the

Unlawful Association Act and adopt all necessary measures and mechanisms to

ensure workers’ and employers’ rights, in line with ILO Convention No. 87 on

Freedom of Association and the Protection of the Right to Organize.

52. The freedoms of opinion and expression, assembly and association are

essential for the functioning of a democratic society. They are fundamental rights

enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in international human

rights treaties, including those to which Myanmar is party: the Convention on the

Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination against Women and ILO Convention No. 87 on Freedom of

Association and the Protection of the Right to Organize. The 2008 Constitution also

provides for freedom of expression, opinion and assembly. The Preamble (para. 8)

provides for justice, liberty and equality. Article 6 (d) declares that the basic

principles of the Union are the flourishing of a genuine, disciplined, multi-party

democratic system. Article 406 (a) and (b) state that a political party shall have the

right to organize freely and to participate and compete in elections. Article 354

states that every citizen shall be at liberty to express and publish freely their

convictions and opinions, to assemble peacefully without arms and to form

associations and organizations.

53. The right to freedom of expression is linked to the role of the media. The 10-

point reform agenda outlined by the President to Parliament included amending

some journalism laws in line with the provisions of the Constitution. During the

Special Rapporteur’s mission to Myanmar, some interlocutors noted that media

censorship had eased. In August 2011, slogans criticizing foreign media were

removed from Government newspapers. In September 2011, an article by Daw Aung

San Suu Kyi was published in a local journal, her first publication in 23 years.

Nevertheless, the Special Rapporteur has received reports of continuing restrictions

A/66/365

11-50111 15

placed on the media. For example, news outlets inside Myanmar have been required to

publish only State-run newspaper accounts about fighting between the Government

and the Kachin Independence Army in Kachin State. As of 10 June 2011, publications

focusing on sports, health, the arts, children’s literature and technology no longer

need to gain approval prior to publication, but copies must be submitted to the Press

Scrutiny and Registration Division afterwards. Publications focusing on news,

crime, education, economics and religion must still be presented to censors prior to

publication.

54. The Ministry of Information issued a regulation requiring publications to

deposit 5 million kyat (around US$ 5,882) with the censorship board, with the

stipulation that if they violated rules three times, the money would be seized upon a

fourth violation. According to reports, a new oversight board under the Ministry of

Information has been established to investigate violations. On 7 June 2011, the board

issued notifications that include No. 46, prohibiting publication and distribution of

material that is contrary to the Three National Causes (non-disintegration of the

Union, non-disintegration of national solidarity and perpetuation of national

sovereignty); the Constitution; or the Official Secrets Act; that is damaging to relations

among ethnic national races or religions; that upsets peace and tranquillity or incites

disturbances; and that exhorts members of the armed services to commit traitorous acts

or undermines the performance of public service duties. The Special Rapporteur

highlights that these vague but encompassing restrictions are similar in nature to the

laws that have been used to convict prisoners of conscience for many years.

55. The Special Rapporteur was informed by the Minister for Labour, Aung Kyi,

that a draft trade union law had been submitted to the Bill Committee in Parliament

for consideration. ILO has provided assistance in drafting the law, including through

a mission to Myanmar by an ILO consultation team in July 2011. The Special

Rapporteur welcomes this development and hopes that the draft law, as adopted,

will conform to international standards.

56. President Thein Sein has publicly acknowledged that many individuals and

organizations, both inside and outside the country, do not accept the new Government

and the Constitution. He has, however, asserted the importance of showing goodwill,

and urged these actors to take part in elections in accordance with the democratic

process and exercise their constitutional rights by legitimate means if they desired a

change to the Constitution. Recently, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Wunna

Maung Lwin, also stated that those willing to participate in the deliberations of the

future of the nation should form a political party, be elected and take part in the

Hluttaws as representatives of the people, in accordance with the Constitution.

57. Questions remain over the status of the National League for Democracy, which

the Government has declared an illegal party over its failure to re-register to

participate in the 2010 elections. The National League for Democracy has since

exhausted legal appeals against its official dissolution. On 29 June 2011, The New

Light of Myanmar reported on the letter from the Ministry of Home Affairs to Daw

Aung San Suu Kyi, stating that her party was breaking the law by maintaining party

offices, holding meetings and issuing statements. The letter stated ‘‘If they really

want to accept and practice democracy effectively, they are to stop such acts that

can harm peace and stability and the rule of law, as well as the unity among the

people including monks and service personnel’’. The Special Rapporteur notes that

the National League for Democracy and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi represent key

A/66/365

16 11-50111

stakeholders, who need to be included in the political process. National reconciliation

requires real dialogue with all relevant stakeholders. Therefore, he welcomes talks

between the Minister Aung Kyi and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi on 25 July and 12 August,

and notes with appreciation the meeting held with President Thein Sein on 19 August,

which resulted in public statements on the need to cooperate. He hopes that these

talks will further substantive engagement between the Government and important

political opposition stakeholders.

58. The Special Rapporteur notes with appreciation that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi

was able to travel, without incident, outside Yangon for the first time, from 4 to 8 July

2011, when she made a private trip to Bagan, and then on 14 August 2011 when she

travelled to Bago to meet with supporters, open two libraries and to give public

addresses. Nevertheless, he reiterates that Daw Aung San Suu Kyi should be

allowed to travel without restriction and to be allowed to exercise her right to

freedom of expression and freedom of association and assembly, and that these

freedoms should be the general rule rather than an exception.

D. Economic, social and cultural rights

59. The President’s inaugural speeches made several commitments in the area of

economic, social and cultural rights, and his 10-point reform agenda includes the

safeguarding of farmers’ rights, creating jobs and safeguarding labour rights,

overhauling public health care and social security, raising education and health

standards and promoting environmental conservation.

60. In addition to these commitments, the Special Rapporteur is encouraged to

note recent initiatives, such as the enactment of new investment legislation; the

holding of another national workshop on rural development and poverty alleviation,

in May 2011, and the development of an action plan (covering the period 2011 to

2015) on this issue; the Third Development Partnership Forum, held in June 2011,

jointly organized by the Government and the Economic and Social Commission for

Asia and the Pacific; and a national-level workshop on economic reform and

economic development, held in August 2011, to which Daw Aung San Suu Kyi was

invited. He also takes note of the Government’s stated intention to reduce the

poverty rate in Myanmar from 26 per cent to 16 per cent by 2015.

61. In his report to the Human Rights Council in March 2011 (A/HRC/16/59), the

Special Rapporteur began to explicitly address economic, social and cultural rights:

those human rights relating to the workplace, social security, family life,

participation in cultural life and an adequate standard of living that includes access

to food, water, housing, education and health care. He noted that the failure to

address systematic discrimination and inequities in the enjoyment of these rights

will undermine efforts to build a better future for the people of Myanmar.

62. During his mission to Myanmar, many interlocutors underscored the extent to

which the people have been deprived of economic, social and cultural rights,

throughout the country, but particularly in the ethnic border areas. This is closely

linked to the need to immediately address Myanmar’s long-standing social,

economic and development challenges. Concerns regarding the availability and

accessibility of education and health care were specifically highlighted, as well as

the need for the teaching of ethnic minority languages in schools in minority areas,

reflecting issues that the Special Rapporteur has raised previously.

A/66/365

11-50111 17

63. A recent survey conducted by the United Nations Development Programme, in

cooperation with the Government’s Ministry of Planning and Economic Development,

the United Nations Children’s Fund and the Swedish International Development

Agency, found that Chin State remains the poorest State among 14 regions and States

in Myanmar, with 73.3 per cent of the people below the poverty line, while Kayah

State had a poverty rate of 11.4 per cent, Yangon region had a rate of 16.1 per cent,

and Rakhine State, with a rate of 43.5 per cent, was the second poorest.

64. Other concerns highlighted land and housing rights, particularly with respect

to the impact of infrastructure projects; land confiscation by the military for

barracks and military camps, the production of food for soldiers, and subsequent

designation of “high security areas” prohibiting people from access; natural resource

exploitation; deliberate population transfers to change the demographic make-up of

certain areas, including Northern Rahkine State; and development-induced

displacement. Violations of land and housing rights result in poverty, displacement

and ruined livelihoods, but also the destruction of cultures and traditional

knowledge. Estimates of the number of people forcibly displaced in Myanmar since

1962 owing to natural disasters, armed conflict and increasingly, to infrastructure

and development projects, place the figure over 1.5 million.

65. During the Special Rapporteur’s visit to Mae Hong Son, in Thailand, in May

2011, Karenni civil society organizations highlighted the problem of infrastructure

projects in Kayah State. The construction of the Moebye dam and the Lawpita

hydropower plant appear to have been a factor in the military’s actions in 1996,

leading to massive displacement of populations to relocation sites and over the

border into Thailand. At least 183 villages, covering at least half of the entire

geographic area of the State and with an estimated total population between 25,000

and 30,000 people, were ordered on short or no notice to move to various relocation

sites, in order to cut off civilian support for the Karenni National Progressive Party

after a ceasefire agreement was breached in June 1995. While most of the power

produced by these projects goes to central Myanmar, with few benefits for local

villagers, these residents have been victim to forced labour, including providing

sentry duty to guard the structures, and made vulnerable to landmines used to

protect the properties. Neither environmental nor social impact assessments were

done for the projects. Meaningful consultation with communities likewise did not

take place, although village headmen in affected communities apparently were

provided with income-generating opportunities.

66. In 2010, the Government agreed to the construction of three new dams on the

Salween river in Kayah State, with the Chinese State-owned Datang Corporation,

and surveys are reportedly being undertaken by engineers with army escorts. There

is great concern for people living in the area, particularly for the indigenous Yintale

Karenni, with only 1,000 members remaining, who are threatened with forced

relocation, land confiscation and other human rights abuses. The Special Rapporteur

recalls that a number of articles in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples explicitly provide for free, prior and informed consent. Article

32 (2) requires States to “consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous

peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain

their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their

lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the

development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources”. The

A/66/365

18 11-50111

Declaration is also explicit that no relocation of indigenous peoples should take

place without consent.

67. Tensions that led to the current armed conflict in Kachin State appear to have

been exacerbated by the Government’s approval of the construction, by China, of

seven major hydroelectric projects on Kachin lands. While the projects will involve

significant population displacement, destruction of local livelihoods and flooding of

large parts of Kachin territory, the concerns of the ethnic group appear, to date, to

have been largely ignored. In March 2011, the Kachin Independence Organization sent

a letter to central authorities in China, detailing its concerns and seeking support in

resolving the issue. Likewise, in Kayin State where the Hatgyi Dam is planned,

increased fighting has led to thousands of new refugees fleeing to Thailand.

68. There appear to be more new projects in development. More than 25 large

hydropower dams are being built or planned on all major rivers, with investment

mainly from neighbouring countries to whom most of the power will be exported,

despite only 13 per cent of Myanmar’s population currently having access to

electricity. The planned dams are all located in ethnic regions. Other projects

include a deep sea port, gas and oil pipelines and mines involving multinational

companies from China, India, the Republic of Korea, Thailand and other countries,

including from Europe and North America, despite sanctions which do not permit

service contracts. Myanmar requires strong rule of law in order to guarantee the

rights of the people in the context of these infrastructure projects. Communities

need to be consulted in a meaningful way, which does not appear to have been done

in most cases. Revenues from these projects should be recorded appropriately and

be used to benefit the people of Myanmar for the realization of their economic,

social and cultural rights. The private companies that are involved in these projects

also have a responsibility to not be complicit in human rights abuses.

69. Whereas the Government was directly responsible for economic projects prior

to 1988, private local commercial interests with strong links to the military have

since emerged, complicating somewhat the respective roles of these companies and

the Government in their legal complicity in human rights abuses. For example, on

18 December 2010, the Htoo construction company, owned by a powerful

businessman in Myanmar with strong connections to the military, cleared the land of

a group of farmers, which was under agricultural use, for the construction of a road

to the site of a caustic soda and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) factory in Magway

Division. On 4 February 2011, four farmers lodged a complaint about attempts by

the Htoo Company to acquire their land at a greatly undervalued amount; their

complaint was rejected in court on the grounds that the land was being acquired for

a Government project, even though the company is private. Subsequently, a gang of

about 20 men attacked a group of the farmers, injuring two of them, and a series of

criminal charges were filed against the farmers. The case went to court very quickly

and the farmers were convicted.4 Given the wave of privatizations last year, some

under questionable circumstances, along with the new Government’s plans to

accelerate economic development, the Special Rapporteur fears an increase in land

confiscation and other forms of coercion by private sector actors in collusion with

the military and Government.

__________________

4 Asian Human Rights Commission, Urgent Appeal Case: AHRC-UAC-073-2011, 7 April 2011,

available from www.humanrights.asia.

A/66/365

11-50111 19

70. While Myanmar is not party to either of the core international human rights

covenants, the right to adequate housing is recognized in article 25, paragraph 1, of

the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as well as in the two treaties that

Myanmar has ratified: in article 14 of the Convention on the Elimination of All

Forms of Discrimination against Women and in article 27, paragraph 3, of the

Convention on the Rights of the Child.

71. The Government’s obligations to realize the right to adequate housing does not

require provision of housing but facilitation of the conditions, through law and

policy, for citizens to have access to adequate housing. The Government has the

obligation to not forcibly evict people and to protect people from being forcibly

evicted by third parties. The Commission on Human Rights, in its resolution

1993/77, stated “that the practice of forced eviction constitutes a gross violation of

human rights, in particular the right to adequate housing”.

72. In this context, the Special Rapporteur reminds the Government of the victims’

right to restitution, a principle of restorative justice, providing every refugee and

displaced person the right to return to their former homes and lands and to have

their homes and lands, with repairs for any damage or rebuilding of destroyed

property, under the Principles on Housing and Property Restitution for Refugees and

Displaced Persons, adopted in 2005 by the Sub-Commission on the Promotion and

Protection of Human Rights, in its resolution 2005/21. He notes that restitution

rights are not limited to people with land titles, but also renters and other legal

occupiers of land. If return to the old home or land is not possible, displaced persons

have a right to compensation for their loss and/or a new house and/or land. The

Government needs to adopt relevant rules and policies, in this regard, which ensure

an independent and impartial process.

V. Truth, justice and accountability

73. As stated in previous reports, the Special Rapporteur is concerned that a

pattern of gross and systematic violations of human rights has existed for many

years and continues today, although a new political system is being established. He

reaffirms that justice and accountability measures, as well as measures to ensure

access to the truth, are essential for Myanmar to face its past and current human

rights challenges, and to move forward towards national reconciliation.

74. The Special Rapporteur reiterates that it is primarily the responsibility of the

Government of Myanmar to address this problem and to end impunity. Investigating

and prosecuting those responsible for serious violations of international human

rights law and international humanitarian law is not only an obligation but would

deter future violations and provide avenues of redress for victims. If the

Government fails or is unable to assume this responsibility, then the responsibility

falls to the international community. Accordingly, the Special Rapporteur has

previously recommended that the international community consider establishing an

international commission of inquiry into gross and systematic human rights

violations that could amount to crimes against humanity and/or war crimes. He

makes clear that this is only one option for ensuring that justice is dispensed,

accountability is established, and impunity is averted.

75. An international commission of inquiry, appointed by ILO in 1997, found in

1998 that the “obligation to suppress the use of forced or compulsory labour is

A/66/365

20 11-50111

violated in Myanmar in national law as well as in actual practice in a widespread

and systematic manner, with total disregard for the human dignity, safety and health

and basic needs of the people”. The Government, which had been invited to take

part in the proceedings, abstained from participating in the inquiry and did not

permit the commission to visit the country. The commission received over 6,000

pages of documents and heard testimony by representatives of non-governmental

organizations and over 250 eyewitnesses with recent experience of forced labour

practices. The outcome of the commission’s investigation into forced labour

includes an acknowledgement of the problem and some efforts to address it,

including through subsequent active cooperation by the Government with ILO

through a supplemental understanding. Such a positive outcome could likewise be

helpful to the Government in confronting wider human rights and humanitarian law

violations.

76. During his mission to Myanmar, the Special Rapporteur repeatedly highlighted

the importance of investigations into alleged human rights violations being carried

out by an independent and impartial body, in order to establish the facts. In this

connection, he was again informed that the Myanmar Human Rights Body, under the

chairmanship of the Minister for Home Affairs, had established a team to investigate

human rights violations whenever they were lodged by citizens and to take punitive

actions against violators. He notes, however, that the Myanmar Human Rights Body

does not operate under any legislation but under the terms of Notification 53/2007,

which sets out in three paragraphs the body’s composition and broad terms of

reference: to examine and make proposals on work related to the United Nations and

international human rights; to examine and make proposals on the establishment of a

human rights commission in Myanmar; and to set up working groups as necessary. No

reference is made to any investigative capacity or complaints receiving mechanism.

77. During his mission, the Special Rapporteur received information that the

Government intended to establish a national human rights institution. On 6 September

2011, the Government issued Notification 34/2011 on the formation of the Myanmar

National Human Rights Commission “with a view to promoting and safeguarding

fundamental rights of citizens described in the Constitution”. The Special

Rapporteur has also received information that the Government intends to research

the role and terms of reference of other human rights commissions established

during democratic transitions.

78. The Myanmar National Human Rights Commission is composed of 15 members,

the majority of whom are former Government officials. There are many questions

about the role and functioning of such an institution and whether it would comply,

in terms of independence and effectiveness, with the Principles relating to the Status

of National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (Paris

Principles), which were welcomed by the General Assembly in its resolution 48/134.

In this respect, the Special Rapporteur notes that an independent, credible and

effective institution that complies with the Paris Principles could be an important

mechanism for receiving complaints and investigating violations, thereby playing a

central role in human rights promotion and protection in the country.

79. The Special Rapporteur emphasizes that ultimately the institutions and

instruments in Myanmar available for investigation of human rights violations

should meet international standards. Moreover, the issue of access to remedies and

reparations must be addressed. The right to effective remedy is recognized under

A/66/365

11-50111 21

international human rights law and has been detailed in General Assembly resolution

60/147, by which the Assembly adopted the Basic Principles and Guidelines on the

Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International

Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law.

80. The Special Rapporteur perceives that there is a growing understanding and

recognition in some areas of the Government and among other stakeholders inside

the country about the major responsibilities of the authorities in respect to truth,

justice and accountability measures for past and ongoing gross and systematic

human rights abuses. He again encourages the Government to demonstrate its

willingness and commitment to address these concerns and to take the necessary

measures for investigations of human rights violations to be conducted in an

independent, impartial and credible manner, without delay.

VI. International cooperation

81. The Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Myanmar, Mr. Vijay Nambiar,

has been able to continue the Secretary-General’s good offices dialogue through his

visits on 27 and 28 November 2010 and from 11 to 13 May 2011. The Special

Rapporteur remains in close contact with the Special Adviser.

82. The Government of Myanmar participated actively in the universal periodic

review process with the consideration of its report in January 2011 and the adoption

of the outcome in June 2011.

83. OHCHR plans to conduct a human rights training workshop for Government

officials during 2011. This follows a similar training workshop for Government

officials, held in 2010.

84. The Special Rapporteur welcomes the return of the International Committee of

the Red Cross (ICRC) to Myanmar with the visit of three officials from the ICRC

water and habitat engineering department to three prisons (Myaungmya prison,

Moulmein prison and Pa-an prison), on 1 and 2 July 2011. He again urges the

Government to allow full access of ICRC to prisons and to prisoners, according to

its standard procedures applied worldwide.

85. ILO has provided assistance to the Government on a draft trade union law. The

Special Rapporteur hopes that the legislation, as adopted, will be in line with

Myanmar’s international obligations under Convention No. 87, which Myanmar has

ratified.

86. The President noted in his inaugural speech that the Government intends to

work in cooperation with international organizations, including the United Nations

and non-governmental organizations in the education and health sectors.

87. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

has noted a relative improvement in its ability to secure permissions for and

facilitate the implementation of its activities in Myanmar, particularly its aid

projects in Rakhine State. Collaboration with the Government for future planning

and resolving UNHCR concerns in the field has also improved comparatively.

UNHCR both directly and indirectly collaborates with local Government bodies in

support of formal and informal education; health; water, sanitation and hygiene; and

infrastructure development projects.

A/66/365

22 11-50111

VII. Conclusions

88. This is a key moment in Myanmar’s history and there are real

opportunities for positive and meaningful developments to improve the human

rights situation and deepen the transition to democracy. The new Government

has taken a number of steps towards these ends.

89. Yet, many serious human rights issues encompassing the broad range of

civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights remain and they need to be

addressed. The new Government should intensify its efforts to implement its

own commitments and to fulfil its international human rights obligations.

90. The Special Rapporteur holds the view that justice and accountability

measures, as well as measures to ensure access to the truth, are fundamental for

Myanmar to face its past and current human rights challenges, and to move

forward towards national reconciliation and democratization. In this context,

the Special Rapporteur reiterates that it is essential for investigations of human

rights violations to be conducted in an independent, impartial and credible

manner, without delay. The new Government should signal its willingness and

commitment as soon as possible through concrete action at the domestic level in

this regard. The international community should be ready to consider those

steps necessary to help Myanmar to fulfil its international obligations, which

could include a commission of inquiry or other forms of technical assistance.

91. The international community needs to remain engaged, closely follow